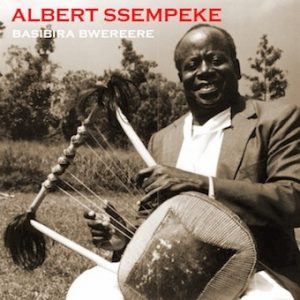

Albert Ssempeke was not only a gifted musician with a deep knowledge of the music of the royal court of the king of Buganda but also a patient teacher from whom I, my son Andy and many students were privileged to learn much about kiganda music. When working in Uganda during the 1960s I knew little about Ssempeke other than obtaining a few recorded items performed by him at a concert in the Uganda Museum, but after my return to Uganda in 1987 we became good friends and I benefitted enormously from his willingness to share and discuss his great musical knowledge and ability.

The following early account is little known and deserves re-publication.

The Autobiography of an African Musician

Klaus Wachsmann’s translation of Albert Ssempeke’s “Autobiography of an African Musician” from Music Educators Journal, February 1975, © copyright by the National Association for Music Education. Reprinted with permission.

Introduction

Albert Ssempeke’s autobiography was recorded on the spur of the moment in Uganda. It was spoken in Luganda, the language of the Baganda, a nation of some two million people within the Republic of Uganda in East Africa. Ssempeke is a child of a generation whose members have learned to take in their stride the many changes that their society has gone through in their lifetimes. He is untouched by the passions of politics and yet committed, conscious of the heritage of his own people and yet interested in innovation, a grassroots musician and yet at home in many different contexts – in short, a real musician

His autobiography vividly portrays his personality and his place in his society, and it also gives the reader a feeling for his culture as seen through the eyes of an active musician. He came to Northwestern University in 1971 under the auspices of the Program of African Studies and the School of Music to teach for one year. He befriended students from all parts of the academic community, but especially those within the interdisciplinary ethnomusicology program that the university had adopted in 1968. He was a resource person, a scholar, a performer, a teacher and a friend.

Klaus P. Wachsmann. Professor of Music History and Literature

Northwestern University

———————-

My name is Albert Ssempeke.

I belong to the Nkima (monkey) clan, and I am a grandson of Kibiikyo. My father’s name is Semioni Balagadde. Among other things, my father had a job in the Lubiri [1]. He was the keeper of the Ssekabaka gate until old age, when he retired to his home in the country. While he was still working in the Lubiri, my father went out of his way to visit the royal abalere[2], and the more he listened to their playing the more he grew to like the endere and the more he wanted to play it himself. He did his best to learn how to play, but he did not intend to get absorbed too deeply. He was satisfied with playing at home before us, his children, to our great pleasure.

As time went on and we grew older, my younger brother Ludoviko Serwanga, started to imitate a song that father used to blow on the endere . However, that boy never played on father’s flute, out of respect for the old man: instead, he used the stalk from the leaf of an eppaappaali (pawpaw or papaya) tree. The leaf stalk of the eppaappaali is hollow inside: my brother cut it in the shape of the flute endere , with four holes. He began by playing in our father’s style, trying to make sure that the tune was the same as our father’s. After mastering the tune, he often had a chance to perform before old friends of my father when they came to visit and talk about the old days.

On these occasions they would find Serwanga practising on his endere . They would go up to him and say:

“Owange[3] Serwanga, do you know how to play the endere ?” “Oh, well, I am trying to learn.” “Play us a tune.”

And so he would play the endere for them, and I saw how these respectable people reached into their pockets, got out some money, and offered it to him: “Go and buy some bread for yourself.”

You see, in those days to eat a piece of bread was quite a treat; it was considered a delicacy.

This aroused envy in me, and I thought “Yii![4]. How can this child be making money while I, his elder brother, just sit here idly?”

And so I, too, decided to take up the flute, and I imitated the tune that he played. I started by joining him in whatever song he would play. I would follow him carefully. He would play a section, and then I would play it after him. Among the three of us – my father, my young brother, and myself – nobody told the other in words what to do. It came about just by knowing the tune the way it went, and then one would try and get it on the endere through trial and error until it had been learned.

Eventually, I mastered the song that my brother used to play. This particular song was called “Bamutta Olabye”[5], and it went like this:

to le ro le ro

to lo le ro li

to lo le ro le ro li

to lo le ro li ri

to lo le ro le ro li

to lo le to li ri to le ro le ro li

to le ro li ri [6]

Eventually, when I felt I was able to play this song, matching the tune that my younger brother played, it made me exceedingly happy.

From then on, whenever we listened to gramophone recordings, we practised the tunes together. In those days there were very few gramophones around, but wherever there was one in the neighbourhood, we would go there to listen to the recordings. Every now and then we would hear a song in an endingidi[7] ensemble in which the endere was employed. This is so because for music to entertain at parties the endingidi usually combines with the endere . We would then return home and try on our flutes the songs that we had heard on these recordings. We found that we made good progress as we went along.

At this time I also started to go to a baptism class in order to get a baptism name. This was in the year 1937, and it took me one year to get baptised. In 1939, after finishing baptism class, I enrolled in elementary school to learn how to write and count. But because of my great love for musical instruments, I always tried to appear before the minor officials who came to tour our part of the country for inspection.

Some of these people came in the service of Ssabasajja[8]. For example, the Omuwanika w’ebyalo[9] would come around, or the Ssaza (county) chief would come to tour the Ggombolola (sub-county) to see how things progressed.

In our neighbourhood, about four miles from my home, there lived a man by the name of Yeremiya Nkasi, who was one of the endere players in the Lubiri. This man was in the habit of taking walks through our village, and one day he found us playing the flutes. He came up to us and said: “Ooo, muli wano [10], so you play the endere ?” “We try to learn.” “You play on these perishable things?” You see, these eppaappaali stalks did not last for more than, say, a week and three days before they rotted away, and we would have to make new ones. And he said: “I will go to town and get you some real endere .” “That would be good, Ssebo[11]“, we replied.

It wasn’t long before he went up to the city and brought us some endere . When he brought them over to us, he played a song and left us to learn at our own pace. We practised, and eventually we learned it, after he had left. After this, he always came for us whenever there were important people touring the Ggombolola, and he took us to join with some of the endere players from the Lubiri. He could do this because he was the head of a kisanja[12] of the endere ensemble in the Lubiri.

Shortly after this, a man moved to the piece of land next to my father’s. The newcomer’s name was Matiansi Kibirige. As it is the custom for the young people to be quick in making new friends with a newcomer in the village, we paid him a visit. When we looked over his house, we discovered that he had a flute, and so we asked him:

“Owange, so you know how to play the endere ?”

“Yes, I know.”

“Please, may we play it?”

“Do you know how?” he asked.

With this, he passed over the endere to us, and we played.

“Ee[13].” he said. ” You should come here for proper lessons. I want you to be able to play even better than that.” And so we became close friends, to the extent that we even helped him to build his house. We helped him by handing him the fibre with which to tie the reeds. We would begin by practising at 6:30 in the evening and go on to 8:00 at night. In this way, he added to our repertoire by teaching us songs we did not know. The teaching consisted of showing us the patterns of new songs and how to finger them on the endere .

In the year of 1939, Ssabasajja Muteesa toured the counties. This was the very first time that I ever set eyes on the Ssabasajja. It was also the very first time in our lives that my younger brother and I performed together with the royal musicians from the Lubiri. In our part of the world, Ggombolola Mumyuka[14]. Ssabasajja came on tour and slept here, and therefore the musicians from the Lubiri were here, too. Because we were so young, the Katikkiro (prime minister) sent for us. He wanted to know how we had learned to play the endere . Confidently we presented ourselves to him, my younger brother and I, and he asked us to play him a song.

The song he asked for was “Balagana Enkonge.” We were able to play it, and he gave us a reward out of his pocket, which pleased us very much. Even going to school did not make me forget the flute. Rather, my younger brother and I, we kept it up. When people needed us to play, we would ask for permission to leave and go to perform whenever and wherever we were required. The usual occasion was when important people came to tour in these parts. Because they had so little money, my parents were unable to take me very far in school.

I went as far as the fourth grade and then stopped there because money was running low. So I took up a job as a shoe repairer working under a gentleman by the name of Peter Mukasa. He offered to teach me how to make shoes. I worked there for two years, but even while I made those shoes I never neglected the endere .

Now it so happened that a man who lived in our neighbourhood, Mulindwa Israeri, planned to get married. He hired abagoma[15] from Kampala. They were men from the Lubiri; in fact they were from Atyeni Mukasa’s ensemble[16]. However, they did not bring their endere players with them: they brought only the endingidi and the endongo[17] players. But since I was nearby, Mulindwa came to me and said: “Owange, I would like to hire you to come and play the endere at my wedding.”

“But I don’t know the other musicians; I have never seen them before. I don’t know whether they will not play songs that I can’t play.” I replied.

“You just try, and if you fail, it won’t matter.” he reassured me.

“All right.” I said. “I will try.”

I used my skills to the best advantage[18]. Also, my flute, which originally had come from the Lubiri, had the same tuning[19] as the endongo and the endingidi from the Lubiri, so I had no difficulty at all. I was able to play every song they played, even those I had never heard before. Once I had learned the tune, I was able to figure it out on the endere . For this he paid me fifteen shillings, and I was so pleased that I said to myself that I must keep on playing the endere .

I made shoes for two years and then decided to quit. This was after I asked myself one big question, namely: “What capital does a person need to set up on his own in the shoe making business?” The person who was my teacher told me that the tools alone would cost nearly fifteen hundred shillings but in my pocket I could not count even a hundred shillings.

My reply was

“Yii. In this work poverty will kill me,”

and I made up my mind to leave and take up tailoring.

A certain Goan gentleman by the name of Paulo, the owner of the premises on which we conducted our shoe making business called me in and offered to teach me how to use a sewing machine. This Goan did something for me that was incredible: he was willing to instruct me in the use of a sewing machine without charging money. Actually it was the result of the many chats we used to have that he made this offer.

At about the same time when I was learning to sew there was an endingidi player living in a place some seven miles away who had a musical ensemble of his own. This group played for money and got engagements to play for parties. Once during Christmas time they came to my village to play at a party. I asked the endingidi player: “Is there an endere player in your group?” “No there isn’t.” he replied. “Please give me a place in your group. I would like to play the endere with you.”

I pleaded with him.

“Can you do it?” he asked.

“I will try.” I replied.

The next time he had a party to play for, he fetched me. We played well. I made no mistakes to any of the songs they played. Soon I began to feel that the playing of endere was not enough, and I said to myself “Aa. that endongo player, to be sure, I hear everything he does when he plays, why don’t I learn endongo myself?”. Thus whenever he came to the end of his song, I took up his endongo and practised and practised, trying to repeat what he had been playing.

Soon I felt that I began to play his song correctly. This gave me a wonderful feeling. I was learning the endongo and to operate a sewing machine at the same time. Bugutanya’s father was an endongo maker, and therefore I asked Bugutanya to obtain a small endongo for me, for which I could pay him. That endongo was really a small one: they sold it to me for only ten shillings. He tuned it for me properly, and I took it with me to my father’s home. I began to practise, and God did not fail me. He gave to me, and I learned well, and so did my younger brother.

By the time I learned these things, I had also become proficient with the sewing maching. Moreover, my employer who had tought me started to pay me wages, although I was a nonpaying apprentice of his. That is to say, he never demanded any money from me: to the contrary, once he saw that I had learned to sew, he just began to pay me a salary. That salary started at eighty shillings a month. A year later he raised me to one hundred twenty shillings.

One day he asked me a question: “Why don’t you give up playing the endere flute since you have got a job as a tailor here? You see, every Saturday you say ‘I am going for a party engagement.’ And the clothes are never finished. Why?”

I told him:

“Ssebo, I ought to be able to give up the endere, but I cannot do it because although I have learned all these other things, it is the endere that was the very first thing I ever learned. I cannot give it up. There is nothing to compare with the endere:: it comes first. It fed me by bringing in the money that kept me going while I learned all these other things.”

He accepted my reasoning. While I was a member of Balamaze’s endingidi group, I got the idea that since I already knew how to play endongo, why did I not form an ensemble of my own? And so I started. I had an elder brother who played the endingidi. I went to him and said:

“Ssebo, I want us to form an ensemble. I can look for a drummer, and we can form a group of our own.”

He agreed. The understanding was that I was to play endongo, my younger brother was to play endere , and my elder brother was to play endingidi. As for a second endingidi player, I could always get one from elsewhere to be added to our group.

The plan that I thought up worked out well. We started our group. It was in 1948 that I created the ensemble of which I was the leader. We are still together, and at this time we are still going strong. And so I succeeded in combining two things: to be a tailor and to play at parties. The people in my neighbourhood have a lot of confidence in me and my ability to perform at their parties. This is so because once a person comes to me and tells me that he is getting married and wants me to play at his wedding., I always make it a point to go and fulfill my commitment to do the job even if we had made no agreement, as long as we had agreed about the fee.

I pursued my profession in this way when I came here to the Uganda Museum in 1965. It was about 1947 that I became interested in the ennanga. But I had nobody to teach me. I always enjoyed listening to Temusewo Mukasa’s ennanga, both on radio and on gramophone recordings. Once I made an effort to buy an ennanga from Erisa Bugutanya, but when I brought it home, I realized that I did not know how to tune and wind the strings properly[20].

I sat there and tried to figure out how to do it, but I failed and I decided to leave it alone. Later, the harp was just left lying alone.

In 1947, after acquiring a home of my own, I got a wife, and the Lord blessed us with children. One day, I left my ennanga lying about in the house. I went on my duties, and it so happened that my wife was also away. When I returned, I found that the children had got hold of it and thrown it into the fire. It was a very great loss to me, and I said:

“Yii Katonda! [21]. The children burned my ennanga..”

There was nothing I could do. Children will be children; one just has to forgive them. Otherwise, I loved all my music activities. My wife and I are still together taking care of each other, and by now we have eight children.

While I was still pursuing my work as a tailor – the job I worked in for a long time – Evaristo Muyinda[22] came to see me. He said: “Ssempeke, I need you.” For a long time Muyinda and I had been meeting frequently in many places where important people happened to turn up. So we knew each other well, and I often played the flute with him. I get great pleasure from every kind of music including the amadinda [23]. Ee, I would resent anyone disturbing me when I am playing music.

Anyway, when he came for me and said he needed me, I asked: “Where are you taking me?” “You just come. You will find out when I get you there.” he replied. At this time I had a new employer. My old boss – the Goan whom I had used to work for – had died, and so I had taken another job with the Indians. Meanwhile, I had been offered another job by the local school in my neighbourhood as a tailor to make school uniforms

When I arrived at the Uganda Museum, Muyinda introduced me to Charles Sekinto, the curator and head of the Museum. He said:

“All right, let’s go and try. Incidentally, which instruments do you know?”

“I know endere , endongo, and endingidi. These are the instruments that I know.” I replied. “I also know the music of the embaga [24], the baakisimba dance and drum music [25], and the drum parts and styles nankasa, empuunyi, and engalabi.[26]”

He then tested me. I tried my best when he handed me the endingidi, and then the other instruments.

He asked me: “Do you know how to play amadinda?”

“Munnange [27], I know the amadinda only as a listener, but I never tried to play.” I replied.

Oh, he gave me excellent advice: “You should go on learning.” When I got to the Museum, all the instruments were there. I laughed behind my hand; even the ennanga that I could not get before was here, and so were the amadinda and the amakondere [28]. I had heard the amakondere often before in the Lubiri – that was when the people in the Lubiri who played asked me to join them and play there. When I asked my father about this, he answered: “You should wait a bit: you will get there later.”

Once I was at the Museum, I began to feel the pressure. I asked myself: what if they ask me to play amadinda? How can I say that I don’t know? So I began to learn to play amadinda. This was not too difficult for me since I have the ability to hear and remember tunes in my head.

Before very long I found I could play “Olutalo olw’Ensisi” [29], the song that every learner on amadinda gets in his first lesson. I learned it by listening to it with my ears. Then by the same method, I learned another song, and soon I found myself going through song after song. Next I took up ennanga. When Muyinda returned from England, I asked him to show me how it was played. He went through every point with me and showed me how it was strung and tuned. I got well into it and worked on the ennanga on my own, but Muyinda also guided me, showing me how this was done like that and that was done like this.

Up to this hour, today, I am still learning because although I can play ennanga, amakondere, and amadinda, I still need to improve. I would like to see that I can play them much better than I do now. I continue to do all these things, and I would like to see that some of my own children learn to do things of this kind.

This is my life story. Albert Ssempeke

February 1975

——————————–

Footnotes

1 The palace and the enclosure that is the residence of the Kabaka, the hereditary leader of the former Kingdom of Buganda. [return]

2 flute ensemble. [return]

3 “My Friend.” a common form of address of some familiarity or kindness. [return]

4 An exclamation of amazement. [return]

5 A topical song about a Mr. Bamutta, who had started a Farmer’s Cooperative but failed. One version of the song goes as follows: Bamutta, you have seen. You ran out of money. When he checked the Bank. He was left with four hundred. [return]

6 Ssempeke sang these syllables at the following approximate pitches:

to = A,

lo or ro = B or C,

le = D,

li and liri = F or G.

lero = D-C.

Actually, the syllables used were only to, lo, le and li, the letter r being accounted for by the Luganda rule that l becomes r after the vowels e and i. [return]

7 A one-stringed bowed lute. [return]

8 A respectful term referring to the Kabaka: something like “His Royal Highness.”, but literally “the father of men.” [return]

9 Literally “treasurer of the villlages.” an official in the Kabaka’s treasury. [return]

10 Literally “Ooo, you are here.” [return]

11 Equivalent to “Sir”. [return]

12 Kisanja is a period of service in the Lubiri, perhaps six to eight weeks at a time, fulfilled in rotation by the court musicians. [return]

13 An exclamation of astonishment mingled with encouragement. [return]

14 A designation of one of the several sub-districts in the county. [return]

15 Literally “drummer”, however, the term refers here to an ensemble of bowed lutes, flutes, a lyre, and drums. [return]

16 A famous group whose recordings were best-sellers. [return]

17 A bowl lyre of eight strings. [return]

18 The word used here by Ssempeke is obukujjukujju, which implies craftiness in addition to skill. [return]

19 The word here translated as “tuning” is the Luganda omuwanjo. It is much used by musicians: sometimes it refers to something like “scale”, and in this context more specifically to the interval of the octave. [return]

20 Ssempeke uses the complex verb form gyenagituningamu. The loan word “tuning” is clearly recognisable. Ssempeke uses yet another phrase in this sentence – okugirega amalobozi gayo, meaning in this case to stretch the strings to the right pitches. The ennanga is especially difficult to prepare for playing on account of the timbre devices: there is one for each string, and each must be adjusted frequently. [return]

21 Literally “Oh God” [return]

22 Muyinda, a Kabaka’s musician and expert on many instruments, was chief demonstrator of music at the Uganda Museum. [return]

23 A “free key” xylophone of twelve keys tuned in an approximately equidistant pentatonic pattern. [return]

24 A feast, generally, but understood more specifically as a wedding party. [return]

25 A dance rhythm and form specifically Kiganda. [return]

26 The three terms designate members of a traditional drum ensemble, each with its own characteristic timbre and musical patterns. [return]

27 Literally “my friend”. [return]

28 Side-blown trumpets played as a set in hocket texture. [return]

29 Literally “The battle of Ensisi”, a well known song. [return]

——————–

1987

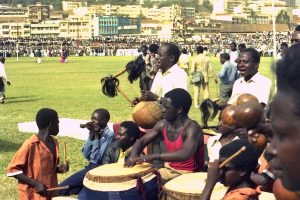

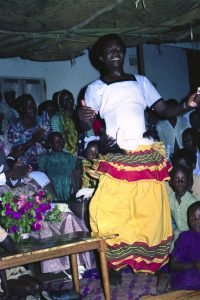

Ssempeke (playing his lyre) and his group of wedding musicians – welcoming Ronald Mutebi, the Ssabataka (heir to the Buganda throne) on his first return from exile in London. Taken at Nakivubo football stadium 12th September 1987.

Ssempeke (playing his lyre) and his group of wedding musicians – welcoming Ronald Mutebi, the Ssabataka (heir to the Buganda throne) on his first return from exile in London. Taken at Nakivubo football stadium 12th September 1987.

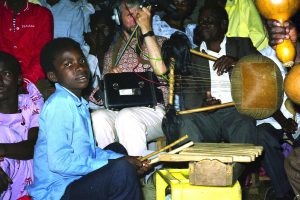

Albert (playing his lyre) is lead singer in this semi-professional group which later that evening drove away to play at a wedding at Bukoloto village some 70km from Kampala. Ten items recorded during this visit are available at BL Sounds (search the site for ‘Ssempeke’ and then down the ‘Date’ column).

The youngest member of the group played a small amadinda.

1988

While revisiting Uganda in 1988 I met with Albert again and invited him to come to Edinburgh to live with us for a semester and to teach at the university’s music department with me. He was an inspiration to all who worked with him, including especially my son Andrew. Some 62 audio items resulting from this visit are available for listening online at BL Sounds (London) and at Makerere and Kyambogo universities,. They include a series of important songs associated with the court of Buganda. He also took advantage of the music department’s studio facilities to multi-track a series of items later assembled for two CDs (Ssempeke!) and, in association with Andrew and me, the teaching pack (Play Amadinda). Both are still available if requested of me.

The following 33 songs were recorded by us during 1987-88 and can be heard by searching the BL Sounds online facility or at the Makerere and Kyambogo University libraries. You will find texts and translations of some of these songs here: Ssempeke!

Abantu balamu

Abe bugerere

Agenda n’omulungi azzawa (7)

Akawologoma (4)

Akayinja kamenya

Alikuwadde AKA Alikuwadde enyanja

Anamwanganga

Asenga omwana tagayala

Balagana enkonge

Bamundabire

Ebigambo ebiwuulire ebgitte ennyumba (2)

Ebyasi bya boona olugudo also known as Mubandusa (2)

Ekyali namakato also shown as Kyalema Nakato

Ekyuma

Enguli (2)

Ensiriba ya munnange (2)

Gganga alula (2)

Kalagala e Bbembe

Laba bwensamba olugere

Musenze alanda

Nnagenda kasana (2)

Nanjobe or (better) Nnanjobe

Njagala nkwagale (4) (also misspelt as Njagala nakwagale)

Nkwagala nkulaba ng’amaanyi

Olwaleero

Omusango gw’abalere

Ssematimba ne Kikwabanga (5)

Ssewaswa kazaabalongo

Tweyanze nnyo

Tweyanzizza

Veronica

Wakadaala yetikka (also misspelt as Wakaala…) (2)

Wavvangaya (2)

Several wedding dance songs were also recorded at Bukoloto.

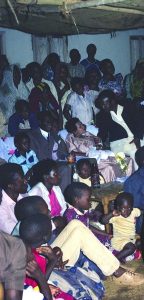

Fun on a visit to the Scottish highlands, with son Ssekitooleko and Andy Cooke.

Fun on a visit to the Scottish highlands, with son Ssekitooleko and Andy Cooke.

Further meetings with Ssempeke during 1992, 1993 and 1994 resulted in another 14 items including some extensive discussions on his repertory..

Finally:-

Watch the Ssempeke family’s promotional film Master Musicians of Buganda.

Eighteen minutes long, this film presents a number music and dance genres genres with Ssempeke performing on a variety of instruments. The final two and a half minutes feature him playing his ennanga (harp), as he sings the famous song Ssematimba ne Kikwabanga (discussed in my blog on Evaristo Muyinda).

Exciting compilation. Very helpful information that Ugandan musicians and music educationists would need to find and read. This man was an icon and such as his kind are not easy to find not only in Buganda and Uganda as a whole.

Thanks for this encouraging comment, James. I wonder what you think too of the Evaristo Muyinda blog. I especially like his explanation of the song Omusango Gw’Abalere

Peter cooke thanx for everything and may the Almighty God bless u mo

I was wondering how I could access the Two CDs play amadinda and Ssempeke

We are so grateful to have you Andy cook you such a blessing to Ssempeke and sons Family and we shall always love you .Am sure jaaja is proud of you mukasa .